Meet Tumamoc's Pioneers & Heroes

Frederick Coville

Volney Spalding

Daniel MacDougal

William Cannon

Burton Livingston

Godfrey Sykes

Francis Lloyd

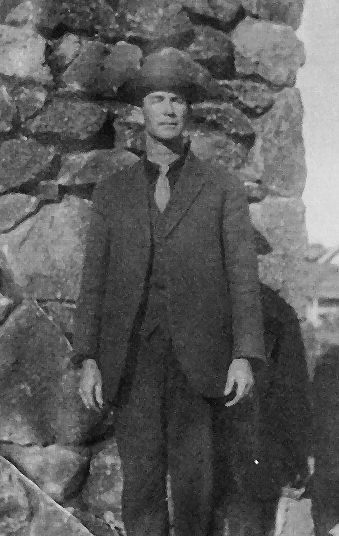

Burt Bovee

Forrest Shreve

Effie Spalding

Ray Turner

Paul Martin

| |

Photograph courtesy of |

In 1901, a lanky tubercular young father named Burt Bovee, under doctor's orders, left his wife and family in Pennsylvania and moved to Tucson in search of good air for his lungs. He was not a scientist and we do not know exactly when he began working at the Carnegie Desert Botanical Laboratory. But he and his family lived nearby at 803 West Congress St. and we know he began his work with the lab at least by 1906 thanks to a photograph that shows him with Francis Lloyd (whose presence at the lab was restricted to the years 1904-1906). He became, in the words of Director D.T. MacDougal, the lab's "general factotum." On 22 May 1911, MacDougal wrote the president of the Carnegie to defend Burt Bovee's value to the lab: We employ Mr. B. R. Bovee as a general factotum, janitor and messenger, who with his saddle horse rides to all of our buildings and structures here early every morning, giving us a half day's service at the rate of $55.00 per month. He accompanies all mountain expeditions with his horse as packer, and when thus giving the entire day renders an account for extra services. And Burton Bovee's importance to the Hill grew and grew. In 1920, when Daniel MacDougal absconded to Carmel, CA, without resigning his position as director, he maintained an absentee directorship through Burt Bovee. Bovee took various scientific measurements and wrote to Carmel each week. He died in 1930, having forgotten to retire. |

|

Bovee collected only one plant specimen during his many years on the Hill, a shrub which now is held safely in the Herbarium of the U of Az. His real biological passion was beetles, a fondness he seems to have shared with God according to JBS Haldane. But Bovee’s extensive, beautifully mounted collection of thousands of local beetles disappeared without a trace soon after he died — despite Forest Shreve’s efforts to see it housed at the American Museum of Natural History. | |